Had Stanmore Station not been built in 1932, it is unlikely that the Warren House Estate would exist. For the extension of the Metropolitan (now Jubilee) Line to this new station awoke the previously sleepy village of Stanmore. The 1920s and 1930s saw improved transport communications creating new residential centres throughout Middlesex and the Home Counties, to form a belt that hugged the fringes of London known as ‘Metroland’. With its massive influx of high-income professionals to the area, Stanmore came to epitomise the Metroland ideal; a new social order – one that allowed these middling classes to commute easily to London for work, but to live in the clean, green, healthy dream of semi-rural suburbia. But if Stanmore was still swathes of rolling fields, how were these mobile families to be housed? Enter Irish aristocrat Sir John Fitzgerald. It was because of his flair for speculative property development that, within only four years of Stanmore Station opening, Kerry Avenue, Valencia and Glanleam Roads were born.

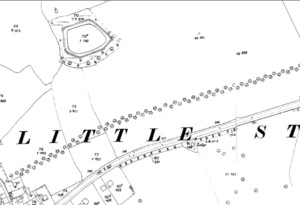

Fig. 1 Map of c.1913-14 showing the London Road surrounded by undeveloped agricultural land [Source: Kerry Avenue Conservation Area Consultation Document]

Sir John had inherited this land in 1922 after the death of his grandmother, Clarissa, wife of financier Henri Louis Bischoffsheim. In fact, the land reserved for development was merely a fraction of the Bischoffsheims’ estate which stretched from their country mansion in Wood Lane, Warren House, through to London Road in the south. The Duke of Chandos built the original Warren House in the 18th Century as a cottage for his warrener, but after debt forced the Duke’s descendants to sell the estate, it came into possession of Sir Robert Smirke, architect of the British Museum. The Victorian era saw the cottage transformed into the Jacobean Revival mansion that we see today. In 1890, the Bischoffsheims acquired the estate and Clarissa, a prominent socialite, held parties there; even hosting King Edward VII in 1907.

Fig. 2 Photograph of Warren House c.1908 [Source: Stanmore Tourist Board]

After inheriting and in anticipation of Stanmore Station opening, Sir John shrewdly granted permits for development of the southernmost part of the estate bordering London Road. Kerry Avenue, ‘a charming country road entry to the pastures and woodland opposite’, would link the station with Sir John’s new development. Valencia and Glanleam Roads springing up on either side would bestow an elegant symmetry on the development, aligned upon the axis of Stanmore Station. The semi-circular green space of Kerry Court, originally lined with white posts, would form the entrance to this grandly-envisaged scheme. Road names were given to recall Sir John’s noble heritage. The Fitzgerald family seat, named Glanleam, was located on Valentia Island off the coast of County Kerry in Ireland.

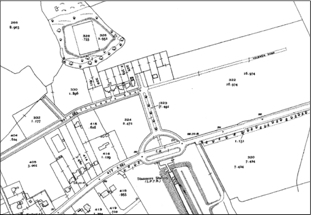

Fig. 3 Map of c.1935 showing the new road layout and houses on Valencia Road [Source: Kerry Avenue Conservation Area Consultation Document]

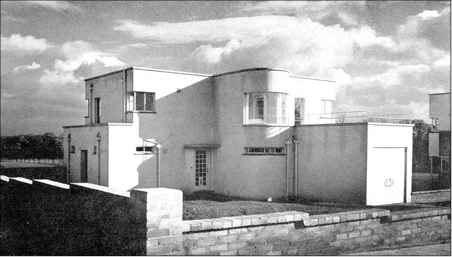

To pull off this speculative project, Sir John daringly decided that the houses in this new enclave should be built in a progressively modern style. The default architectural style of suburban Metroland was ‘Tudorbethan’; bucolic and curbed by ideas of English restraint. But Sir John’s Stanmore commissions were ‘pioneeringly progressive’ according to the famous architectural historian Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, and perhaps the earliest example of a domestic group in London to adopt the principles of the ‘Modern Movement’. Such architecture traces its roots back to Germany’s Bauhaus Arts School, the Swiss and American architects Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, and Cubist architecture. The Modern Movement was essentially a European import, considered the cutting edge of 1930s ideals and technology in design, materials and construction. It dictated that a building’s form should follow its function and that ornament should be eschewed for technological beauty. ‘Functionalism’ meant rectangular shapes, plain rendered walls, steel-framed ‘Crittal’ windows, and curved staircase towers. The flat roof was sacrosanct. Large windows, canopies and sundecks reflected the 1930s Germanic ideal of sun-soaked healthy living. But the Modernist ideal was not necessarily cold or inhuman – greenery was integral to the philosophy; when Kerry Avenue was laid out it was declared that ‘not a tree will be felled or alteration made in the land other than those that may...become absolutely unavoidable’. The leafy island in Kerry Avenue, the grassy verges that extend from every house on Valencia and Glanleam Roads, the panoramic vistas to the East, the wide roads, the lack of road markings, the low walling demarking each house, the low-density nature of the development: the intended atmosphere was of semi-rural seclusion and private tranquillity. Contemporary critics lauded these meticulously planned features for evoking ‘the skilled attention and thoroughness of a long-established garden’. This effect was sealed by the creation of Stanmore

Fig. 4 No. 2 Valencia Road, 1974, showing the striking effect produced by the original steel-framed ‘Crittal’ windows which have since been removed [Source: London Metropolitan Archives]

Nos. 2-10 Valencia Road were the first five houses to be built on the site by architect Douglas Wood, completed in 1934 (Fig. 5). Typical of Modernist design, two of these pairs are linked by garages so that, although each house is asymmetrical, a symmetrical relationship appears when neighbouring houses are viewed together (Fig. 6). Similarly typical are the vertical window strips on the staircase towers. Soft relief to the stark lines is provided by the curved windows and Art Deco sun-deck railings.

Fig. 5 First five houses to be built on Valencia Road (Nos. 2-10), 1934 [Source: London Transport Museum]

Fig. 6 Sleek symmetrical design, Valencia Road, 1934 [Source: London Transport Museum}

In 1936, the celebrated engineer of Wembley Stadium Sir Owen Williams designed the twin apartment blocks at the bottom of Valencia Road – Warren Fields – in a similarly austere fashion.

Fig. 7 Warren Fields designed by Sir Owen Williams, 1936 [Source: Royal Institute of British Architects]

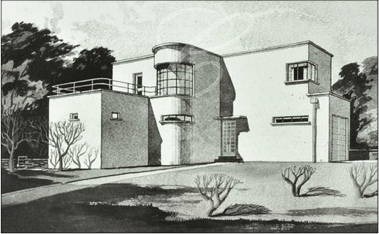

It was lower Kerry Avenue, however, that Sir John intended as the set-piece forming an impressive entrance to the estate. For its six houses, he needed an architect who could devise some of the most impressively advanced architecture of the time. A fashionable Mayfair architect and interior designer, Gerald Lacoste had designed homes for the greatest celebrities of the day, including Gracie Fields and J. Arthur Rank, as well as the most chic fashion houses, including salons for Norman Hartnell and Molyneux. It was imperative in the brief: that the heating and drainage of these houses were economically planned; that the quality of workmanship and materials meant that each house would cost no less than £1000; and that the houses fulfilled ‘the purpose of showing to the house-buying public that speculative building can be treated in an attractive manner, and not necessarily as a continuous repetition of single-fronted houses having no individual character’. These were completed in 1937 and are even bolder than the Valencia Road houses, with starker geometrical forms and a more horizontal emphasis (Fig. 8). No. 6 is a paragon of the progressive machine-made aesthetic (Fig.9). No. 14 Kerry Avenue, built by New Zealander architect Reginald Uren, is equally impressive in its blocky simplicity and has been described as the best building in the area.

Fig. 8 No. 5 Kerry Avenue designed by Gerald Lacoste, perspective drawing by Raymond Myerscough-Walker, 1937 [Source: London Metropolitan Archives]

Fig. 9 No. 6 Kerry Avenue, 1937 [Source: London Metropolitan Archives]

No sooner were these houses built than they suffered bomb damage during the Blitz. Windows were blown out but other original architectural details were scarcely affected; much was simply rebuilt to match.

Fig. 10 Kerry Avenue after bombing, 1941 {Source: Kerry Avenue Conservation Area Consultation Document]

The enduring quality of the Warren House Estate’s legacy can be discerned in some of its post-War houses inspired by Sir John’s commissions, including 14 Valencia Road (1950), and 16 Kerry Avenue (1968) by Gerd Kaufmann. This legacy was considered in an architectural textbook as recently as 2016 with renewed interest in the area coming from a Twentieth Century Society tour that same year. If one stands at the junction of all the roads today and looks north towards Stanmore Country Park, one is still struck by the wide countrified road ahead, by the idyllic grassy verges sloping down to the road on the right and by the way the sun reflects off the snowcrete houses on the left.

The Warren Estate - A History

Benjamin Levy